Boltzmann Brains and the Mind of God

Readers familiar with Jonathan Swift's satirical tale Gulliver's Travels may remember Laputa,

the third country visited by the adventurous Gulliver. A perfectly circular

island measuring close to five miles in diameter, floating above the earth with

the use of magnetism and navigated via Newtonian mechanics, Laputa is ruled not

by small-minded, short-sighted politicians, as in the kingdom of Lilliput, but

by astronomers and mathematicians obsessed with natural science. A secular

prophet of sorts, Swift vividly portrayed the myopic (and often morally

indifferent) visions of certain scientific intellectuals in his day, and in our own. Allan Bloom describes

a preoccupation with all things abstract and theoretical among the Laputians,

along with a herd-like groupthink, which together restrict their understanding of

the everyday world: "The men have no contact with ordinary sense

experiences. This is what permits them to remain content with their science.

Communication with others outside their circle is unnecessary."[1]

These men are science purists who have tapped into the power of

knowledge in order to live in a world above their intellectually inferior neighbors.

But as a result of living in this detached, self-elevated state, they miss some important

aspects of reality. They don't seem to notice or care that their clothes don't

fit, for example, nor even that their wives are committing adultery. The parallels between Laputa and certain sectors of the

twenty-first century scientific establishment are not difficult to see. Many scientists

today indeed hold their science high above all other intellectual endeavors,

and in some cases seem to proffer it as the basis for a new and superior morality. Steven

Pinker, for example, pronounces that science has emerged triumphant over all

other forms of explanation for all observable phenomena:

We

know that the laws governing the physical world (including accidents, disease,

and other misfortunes) have no goals that pertain to human well-being. There is

no such thing as fate, providence, karma, spells, curses, augury, divine

retribution, or answered prayers—though the discrepancy between the laws of

probability and the workings of cognition may explain why people believe there

are.

Notice how Pinker presents the second statement as if it somehow

followed from the first – when of course it doesn't. Pinker's argument holds

only if it is true that "the laws governing the physical world" operate

not only without any goals or purposes, but that they operate uniformly at all

times, places and circumstances. If it cannot be demonstrated that natural laws

are necessarily uniform, or universally binding (and Hume of all people

demonstrated exactly the opposite), then clearly there is nothing to prevent

the actions of providence, or divine retribution or answered prayer. He

continues:

And

we know that we did not always know these things, that the beloved convictions

of every time and culture may be decisively falsified, doubtless including some

we hold today…. In other words, the worldview that guides the moral and

spiritual values of an educated person today is the worldview given to us by

science.[2]

Here Pinker suggests not only that science alone can inform "moral and spiritual values," but that beloved moral and spiritual convictions (such as my belief

that Jesus Christ has risen from the dead and now calls me to serve and honor him) are subject to decisive

falsification – though I notice he doesn't mention how or when I can expect this

falsification to actually occur. But what of his own convictions? Are his

beliefs not also time- and culture-bound? I don't doubt that Pinker and his

colleagues are brilliant theorists, capable of discoursing on topics and

deriving mathematical theorems that people like me can scarcely begin to

understand. But

it seems as if these promoters of "hard science" have forgotten all

the difficult lessons of the logical positivism movement from the previous

century, or the long history of failed scientific theories underlying the

theory of pessimistic meta-induction. At any rate, a monk-like detachment from the

world of everyday life – work, responsibilities, interactions with ordinary

people, economic transactions and so forth – and immersion into the theoretical

world of, say, quantum cosmology, can evidently lead even brilliant theorists

to embrace some wildly speculative, even irrational notions.

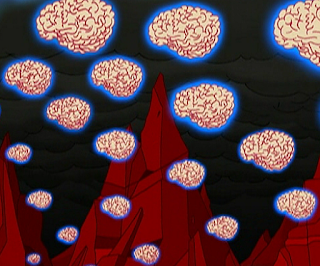

Consider "Boltzmann Brains," the product of a thought

experiment first postulated by the nineteenth-century physicist Ludwig Boltzmann.

According to Boltzmann, the universe is in the low probability, low entropy

state that it is because, well, only in such a state can a brain exist to

observe the universe in the first place. He considered further that a

stand-alone disembodied observer would be far more likely to emerge from any

given thermodynamic state far more often than would an embodied brain from a much more structured environment. Because even in equilibrium (or thereabouts),

fluctuations may occur which give rise to any number of highly improbable

configurations, an infinitely old universe would give rise to a vast number of fully

functioning (if short lived) brains, perhaps complete with apparent memories. Some

have suggested that the Boltzmann Brain hypothesis escapes the implications of

fine-tuning, that our universe has been constructed precisely as it is so that living,

self-aware observers can thrive within it. After all, Boltzmann observers would

be expected to emerge often – at least relative to an infinitely

old universe – from a virtually featureless thermodynamic soup. Cosmologist

Sean Carroll elaborates on some of the disturbing implications of Boltzmann's random

quantum fluctuations:

If

we wait long enough, some region of the universe will fluctuate into absolutely

any configuration of matter compatible with the local laws of physics. Atoms,

viruses, people, dragons, what have you. The room you are in right now (or the

atmosphere, if you’re outside) will be reconstructed, down to the slightest

detail, an infinite number of times in the future. In the overwhelming majority

of times that your local environment does get created, the rest of the universe

will look like a high-entropy equilibrium state (in this case, empty space with

a tiny temperature). All of those copies of you will think they have reliable

memories of the past and an accurate picture of what the external world looks

like — but they would be wrong. And you could be one of them.[3]

Bizarre. Now as Carroll himself points out, actually believing

this is epistemically problematic. We cannot know the Boltzmann Brain scenario to

be true because a theory dependent on random fluctuations is, as he says,

"cognitively unstable. You can't simultaneously believe in it, and be

justified in believing it." But others argue that because it hasn't been

falsified, it remains a viable hypothesis that potentially lends credibility to

a multiverse or eternal-inflationary universe scenario, which in turn may help

explain fine-tuning of our own universe apart from divine intervention. Of

course Boltzmann was only able to concoct his theory under a huge set of finely-tuned

conditions necessary for his own brain to function and thereby observe the

universe. To devise an unfalsifiable theory which suggests that those same conditions

may in fact not be necessary for a

brain to observe a universe seems self-defeating from a scientific-empirical

standpoint. And that's the standpoint which most atheists assume before ever

attempting to defeat the argument from fine-tuning.

Moreover, regions of low entropy could just as easily generate other

wildly improbable entities. In addition

to disembodied brains Carroll mentions dragons, but he may as well

have included invisible pink unicorns, flying spaghetti monsters, and various

other fantastic beings subjected to ridicule by atheists in every other context.

And as mentioned, a disembodied brain

cannot be more likely to spontaneously emerge from a temporarily low entropy region than an embodied brain complete with a

life-supporting environment, because a brain requires a host of quite specific

physical-environmental conditions (a functioning host body, for example) in

order to function, even if for only a few moments. The mere fact, then, that a disembodied

(functional) brain appears "simpler" than an embodied (functional) brain

does not somehow make it less improbable.

All this brings us full circle, back to the strong implications of fine-tuning for theology. Minds in physical universes require brains, which require bodies living in a finely-tuned, life-conducive environment, which requires the careful planning and execution of an unimaginably intelligent and powerful Creator. Our observation of the universe, in short, requires the mind of God.

[1] Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind (New

York: Simon & Schuster, 1987), p. 294.

[2] Steven Pinker,

"Science is Not Your Enemy," The

New Republic, August 6, 2013. https://newrepublic.com/article/114127/science-not-enemy-humanities.

[3] Sean Carroll, "The Higgs Boson vs.

Boltzmann Brains," August 22, 2013, http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/blog/2013/08/22/the-higgs-boson-vs-boltzmann-brains/.

Comments

I see this claim that some people think science can be used to answer moral questions a lot from Christians, and yet when you look at what these people really say, the reality is rather different. This is a great example, where your supporting evidence says nothing at all about morality. Certainly science is being used to discover why we think somethings are right and other wrong, but it is very rare for a scientist to claim that science will tell us what actually is right and what actually is wrong.

Do you have any quotes by Pinker (or anyone) that support your claim that they think science is "the basis for a new and superior morality", because to me it looks like a straw man.

DM: If it cannot be demonstrated that natural laws are necessarily uniform, or universally binding (and Hume of all people demonstrated exactly the opposite), then clearly there is nothing to prevent the actions of providence, or divine retribution or answered prayer.

Whereever there is doubt, there is a gap to squeeze God into.

DM: Here Pinker suggests that beloved convictions (such as my belief that Jesus Christ has risen from the dead) are subject to decisive falsification – though I notice he doesn't mention how or when I can expect this falsification to actually occur.

Are you really so arrogant as to think that all your convictions are necessarily true? You go on to ask:

DM: But what of his own convictions? Are his beliefs not also time- and culture-bound?

Of course! That is the nature of science. Science is humble enough to acknowledge it could be wrong. Something religion can never do. In fact, later in the same paragraph you discuss this yourself. Science is on-going, and bad theories are rejected in favour of better ones. You know this happens, you just choose to spin it as something negative at the end of the paragraph, whilst insinuating that Pinker is wrong for not doing it at the start of the paragraph!

DM: All this brings us full circle, back to the strong implications of fine-tuning for theology.

No it does not. Boltzmann Brains are a solution to the fine-tuning issue. We do not need fine-tuning, we just live in a highly improbably space. Personally, I find Boltzmann Brains unconvincing, but you brought them up.

DM: Minds in physical universes require brains, which require bodies living in a finely-tuned, life-conducive environment, which requires the careful planning and execution of an unimaginably intelligent and powerful Creator. Our observation of the universe, in short, requires the mind of God.

Our observations of the universe indicate minds require brains, and brains require bodies. But hey, if you want to argue for God, I suppose you need to rationalise away that conclusion, and instead tease out something that supports the conclusion you want to reach.

Pix

Sean Carroll is ghettoized and not bright, he;s quite stupid atheists like him because he;'s vocal about proving atheism but he really doesn't know what he's talking about.

Ah, so this is a case of non-scientists reading more into it than is actually there. Scientists do not really say that science can tell us what is right or wrong, but even so it is help to promote the idea that they do.

By the way Joe, does does a "ground of being" tell you what is right and wrong? Care to talk us through the process? Is this like telepathy? Guesswork? What exactly?

Pix

those who try to use genetics as means of disproof of God or natural law clearly imply a prescriptive ethics for science,I said not all scientists make this implication. i also said some directly argue they know what's right such as Harris

By the way Joe, does does a "ground of being" tell you what is right and wrong? Care to talk us through the process? Is this like telepathy? Guesswork? What exactly?

Yes. genetic basis for morality is a good argument for God. Nature can;t have ideas about right and wrong so this idea of moral law writ tenon the heart as the Bible tells us would be explicated through genetic basis for morality,

whatdid i dsay about God as universal mind? not less than persona,l

Pinker: ".. the worldview that guides the moral and spiritual values of an educated person today is the worldview given to us by science." This seems to mean that a scientific worldview -- and in context, nothing else -- guides moral and spiritual values. Is there some important distinction to be drawn between being the only guide for morality and being the basis for morality? (I did try to tone down my statements in an edit, Pix, just for you. :-))

Pix: "Are you really so arrogant as to think that all your convictions are necessarily true?"

The fact that my convictions have not been falsified does not imply that they are "necessarily true." And I can't recall ever suggesting otherwise.

That is not what he is saying. The world we live in today has been heavily influenced by science - for example, you and me communicating over the internet. We get our world view from the world around, a world given us by science.

You are, I assume, an educated person. He is saying that your worldview is due (in part) to science. Your knowledge of cosmology to biology, for example, but your knowledge of philosophy comes via technology, I expect. Without technology, you (and everyone else) would be living like someone in the middle ages, with the worldview of that time.

Is your worldview that of a person living in the middle ages? Of course not! You get your worldview from science, and that informs your morality.

Look, I appreciate this idea that scientists use science to decide what is right or wrong is rife within Christianity, but I invite you to think it though, to look a bit deeper at the truth of the claim.

Exactly how do you think scientists do it? See if you can find where Pinker describes how to use science to say what is right and wrong. Or anyone for that matter.

What do scientists do with these scientifically-derived morals?

Can you find any examples of scientists saying these things are right, and these are wrong? I admit there maybe some fringe examples, but see if their claims are well received by scientists (and where those morals come from).

Can you find any statistics that show scientists tend to be less moral than anyone else? Are their higher rates of murder or adultery, for example? If you are right, then scientists will have quite a different morality to yourself, and that should be obvious in their lifestyles. I somehow doubt that that is the case.

Pix

Question deftly evaded.

Did we acquire our ethics from listening to Jesus? Does that mean that there were no ethics before that? And just what did Jesus have to say about gay marriage? Or slavery?

Oh, no - that's not right. We get our ethics from what God has written into our genetic code. Yeah, that's the ticket. So our inborn sense of morality tells us that slavery is good, because that's what we thought throughput most of human history. But we don't think so now. And that's because God changed the genetic program, right? And some of us think gay marriage is bad, but others don't. So what's up with that?

Walk us through it, Joe.

The "ground of being" became a man? This is the thing you insist is definitely not a person, suddenly becomes a person. This makes as much sense as the colour red suddenly deciding it will enter human history as Captain Scarlet.

And moral law in the heart is consistent with "we just make it up".

Pix

IMS, I think it's time to get some warm milk and a Twinkie and take a nap.

Did we acquire our ethics from listening to Jesus? Does that mean that there were no ethics before that? And just what did Jesus have to say about gay marriage? Or slavery?

try to screw your head on tight. I said we have amoral law written on the heart so we have verification of Christ's teachings, The two work together,and the former serves as a stop-gap until we learn o Christ,

Oh, no - that's not right. We get our ethics from what God has written into our genetic code. Yeah, that's the ticket. So our inborn sense of morality tells us that slavery is good, because that's what we thought throughput most of human history. But we don't think so now. And that's because God changed the genetic program, right? And some of us think gay marriage is bad, but others don't. So what's up with that?

see more loose thinking, first you get upset because you think I'm saying the only moral code is Christianity, The you upset because I assert other moral codes. So what's the deal? you are nuts, you should write speechs or Trump.

Walk us through it, Joe.

you think slavery is wrong don;t you? how do you know it?> moral law on the heart God put it there. We don't enslave people because our hearts say we should. We do it because we are greedy and don'tlisten toour hearts. Religion teaches us to listen,

How would we go about distinguishing between that and an evolved morality that developed from empathy and the need for ever larger societies to co-operative, which would also be partly written in our DNA, and some random guy saying we should be nice to each other?

JH: see more loose thinking, first you get upset because you think I'm saying the only moral code is Christianity, The you upset because I assert other moral codes. So what's the deal? you are nuts, you should write speechs or Trump.

IMS was asking about slavery. It is a good point. Centuries ago, slavery was morally right, now it is not. What has changed? Not our DNA. The words Jesus said 2000 years ago have not changed. So how come we now consider slavery wrong, if morality is based on these two things?

JH: you think slavery is wrong don;t you? how do you know it?> moral law on the heart God put it there. We don't enslave people because our hearts say we should. We do it because we are greedy and don'tlisten toour hearts. Religion teaches us to listen,

So what changed? Was religion not telling us to listen before? Are people more religious than they were back then?

And I am still curious how a "ground of being" can become a man, but not be a person at all.

Pix

JH: try to screw your head on tight. I said we have amoral law written on the heart so we have verification of Christ's teachings, The two work together,and the former serves as a stop-gap until we learn o Christ,

How would we go about distinguishing between that and an evolved morality that developed from empathy and the need for ever larger societies to co-operative, which would also be partly written in our DNA, and some random guy saying we should be nice to each other?

you cant if they are both in-born, of course there is no genetic evidence of genes for morality,that's really way down the road if at all. But given that assumption you can't say it's from God or not from God. What we can say is that without God there's no grounding for moral axioms. empathy doesn't provide adequate grounding, because some people don't have it or learn to turn it off. For example the Publican party,

JH: see more loose thinking, first you get upset because you think I'm saying the only moral code is Christianity, The you upset because I assert other moral codes. So what's the deal? you are nuts, you should write speechs or Trump.

IMS was asking about slavery. It is a good point. Centuries ago, slavery was morally right, now it is not. What has changed? Not our DNA. The words Jesus said 2000 years ago have not changed. So how come we now consider slavery wrong, if morality is based on these two things?

the idea that God hands out all moral precepts at one tie and they don't evolve is big guy in the sky thinking, if God is more sophisticated than a big man in the sky so would his moral precepts be. Of course slavery was not once right and now its wrong, it was always wrong. slave states were rationalizing the issue.

JH: you think slavery is wrong don;t you? how do you know it?> moral law on the heart God put it there. We don't enslave people because our hearts say we should. We do it because we are greedy and don'tlisten toour hearts. Religion teaches us to listen,

So what changed? Was religion not telling us to listen before? Are people more religious than they were back then?

why did you not read the essay I linked to on the evolution of the God concept? Our understanding of God evolves just as does our understanding of all things. Morality is no exception, our understanding not the truth that evolves.

And I am still curious how a "ground of being" can become a man, but not be a person at all.

Pix

tell me why you think a ground of being has to be impersonal?

I more or less agree. Though I would say that in the atheist view, genetics is only a part of our morality, and culture is a rather larger part. Empathy, a sense of fairness, etc. are built-in, and we can see them in small children (and chimps too). But the morality most of us have is largely learn. This is why morality has changed; our culture is developing.

JH: Our understanding of God evolves just as does our understanding of all things. Morality is no exception, our understanding not the truth that evolves.

So you agree there too. But the implication is that most of our morality comes from human thought, or do you think God is actively shaping us, and controlling how society evolves? How would that happen? Does he talk to key individuals, or what?

JH: tell me why you think a ground of being has to be impersonal?

I said "not be a person", based on your "The Super Essential-Godhead (God is 'Being Itself")" essay.

Pix

JH: you cant if they are both in-born, of course there is no genetic evidence of genes for morality,that's really way down the road if at all. But given that assumption you can't say it's from God or not from God. What we can say is that without God there's no grounding for moral axioms. empathy doesn't provide adequate grounding, because some people don't have it or learn to turn it off. For example the Publican party,

I more or less agree. Though I would say that in the atheist view, genetics is only a part of our morality, and culture is a rather larger part. Empathy, a sense of fairness, etc. are built-in, and we can see them in small children (and chimps too). But the morality most of us have is largely learn. This is why morality has changed; our culture is developing.

Religion is filtered though the lens of culture as well that's why all he religions are different.

JH: Our understanding of God evolves just as does our understanding of all things. Morality is no exception, our understanding not the truth that evolves.

So you agree there too. But the implication is that most of our morality comes from human thought, or do you think God is actively shaping us, and controlling how society evolves? How would that happen? Does he talk to key individuals, or what?

I think there's a divine core but it's fleeted through the lens f culture.

JH: tell me why you think a ground of being has to be impersonal?

I said "not be a person", based on your "The Super Essential-Godhead (God is 'Being Itself")" essay.

++

not a person does not mean impersonal. there can still be consciousness and will without person hood.

Let me get this straight. Some people have less empathy or less of a sense of morality, and therefore it can't be a natural phenomenon, but it must come from God.

Stunning logic. We know that nature doesn't produce perfect creatures. But what's God's excuse doing no better than that? And why does the evidence confirm your belief in GodDidIt?

Let me get this straight. Some people have less empathy or less of a sense of morality, and therefore it can't be a natural phenomenon, but it must come from God.

Stunning logic. We know that nature doesn't produce perfect creatures. But what's God's excuse doing no better than that? And why does the evidence confirm your belief in GodDidIt?

think abouit it, it's not magic whatsits right and wrong it's delved rationally from axioms of right and wrong. The axioms are based upon love which is God's character, That is the basis of the good. If there is no God then good is a matter of feeling, you stipulated that empathy is the basis of the moral and empathy is just feeling So if feeling is the basis then they way people feel is ot universal people feel differently among themselves so a person would be justified in killing if he felt anger at someone or justified stealing if we wanted something badly enough. who would say which set of fillings is the right set to have?

at the basis of your view you are really just assert mg the intrinsic rightness o Christian values.

I flatly reject the notion that Cristian values are "right". To think that someone must suffer and die to appease God for the sins of others is nothing short of barbaric - not to mention immoral.

Sheer ignorance.

at the basis of your view you are really just assert mg the intrinsic rightness o Christian values.

I flatly reject the notion that Cristian values are "right". To think that someone must suffer and die to appease God for the sins of others is nothing short of barbaric - not to mention immoral.

I think you are mixed up about the concept of Christian valorous. Values are axiomatic concepts that we value such as friendship, loyalty, goodness, being law abiding, fairness. There is no mention in the Bible of "Christian Values" but what we call "Christian values" are values the Bible affirms that pertain to the Christian message, morality, love, kindness, so on.

Am I just dogmatically asserting that Christian vales are true? No I worked for many years to to develop my ow theory of ethics. I've began writing about it. There's a chapter in my forthcoming books this fall about it.

I would not suggest that you "have no morals." But I would like to know your ethical theory how do you ground your ethical axioms?

I will respond to your questions, perhaps tomorrow or the next day, when I get a little more time.

I would not suggest that you "have no morals." But I would like to know your ethical theory how do you ground your ethical axioms?

Here is my response.